At Caktus, we begin many projects with a discovery workshop. A discovery workshop is an opportunity for our product team to get together with client stakeholders in order to answer three questions:

- What is the problem we are trying to solve?

- For whom are we solving this problem?

- How are we going to solve the problem?

This blog post on product discovery outlines ways to help determine the problem to be solved and answer the question of for whom we are solving the problem.

In short, when discussing the problem to be solved, we talk about:

- Business goals

- Project goals

- Potential constraints and risks

- Success criteria

To find out for whom we are solving the problem we:

- Define user roles for the application

- Discuss user goals

- Identify user pain points

Finally, to identify how we are going to solve the problem, we map out user flows and tasks in an activity called user story mapping.

User Story Mapping

User story mapping is a visualization technique popularized by Jeff Patton that allows product teams to map out an entire application with respect to the different user roles the application must support.

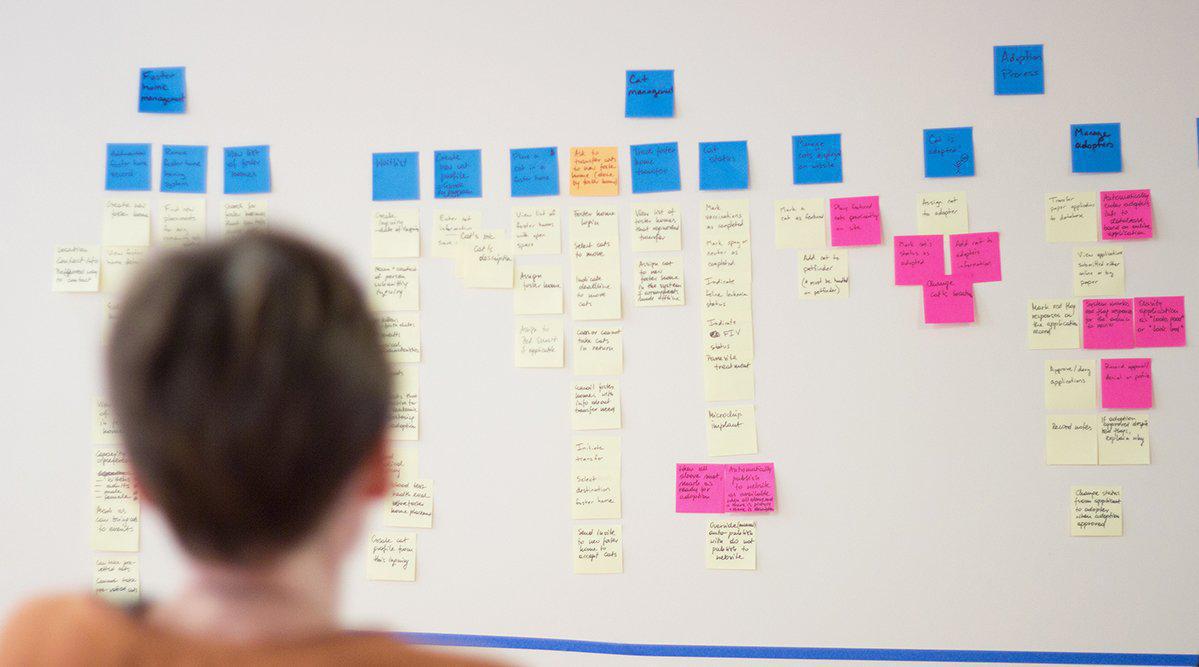

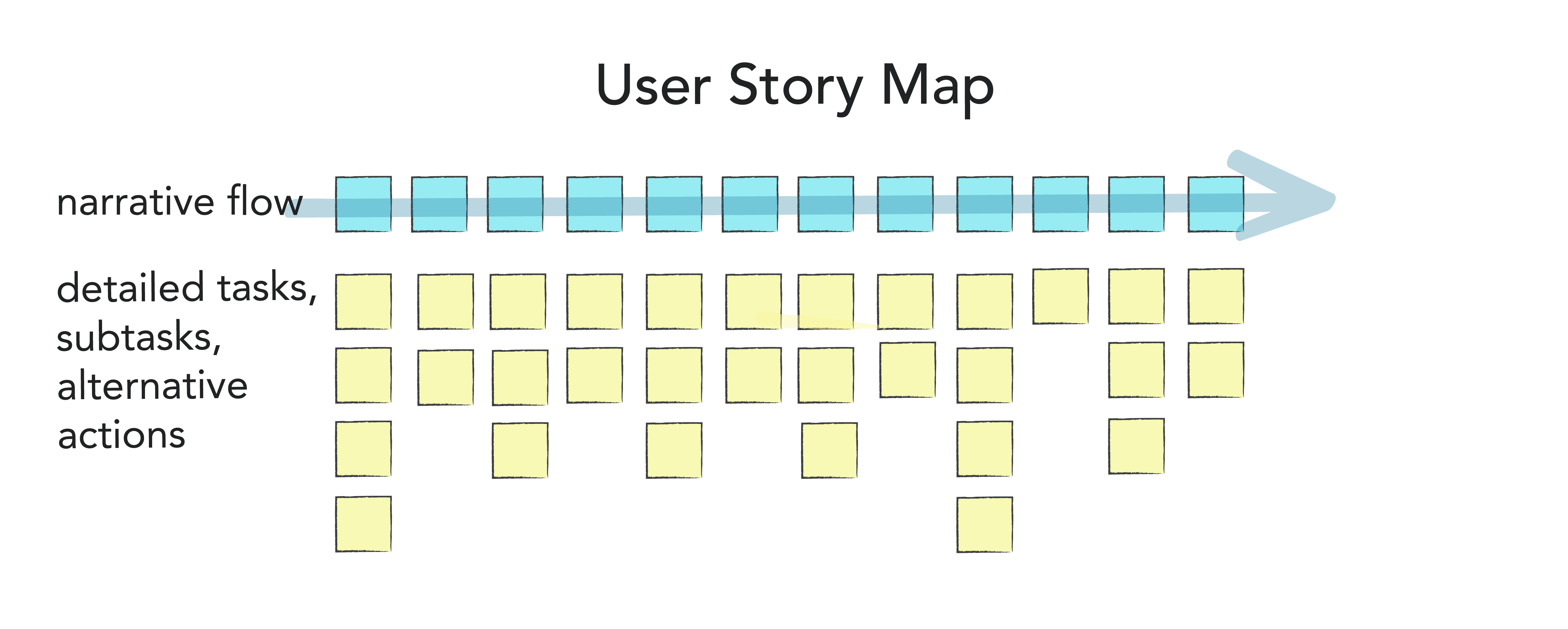

The activity begins by identifying top-level user actions (or user outcomes), writing them out on sticky notes, and arranging them into a row at the top of the user story map. We refer to that top level row as the narrative flow or the backbone of the user story map.

If you imagine building a to-do list application, the narrative flow could include user outcomes such as:

- Manage my account

- Manage my to-do list

- Share my to-do list

Once the high-level tasks have been identified and represented in the narrative flow, we move on to identify detail tasks, subtasks, and alternative ways of accomplishing a task. To distinguish detailed tasks from the narrative flow in the user story map, we write them out on different color sticky notes and add them to the user story map under the relevant high-level tasks.

In the case of this imaginary to-do list application, under “Manage my account,” we could list detail tasks such as:

- Create my account

- Edit my account

- Delete my account

and subtasks such as:

- Edit my contact information

- Edit my password

- Edit my avatar

After the entire application is mapped out in this way, we identify a list of most valuable features. We do that by asking stakeholders which features the application can go live without and still deliver its essential business and user value. We draw a prioritization line across the map, consider each user story in the map, and move sticky notes that represent non-essential stories (or features) under the priority line.

The user story mapping activity leads us to a planned-out application and a list of most valuable features. The prioritized user story map also becomes the first iteration of the project backlog. (A backlog is a list of features or technical tasks that are necessary and sufficient to complete a project.)

Writing User Stories

After the discovery workshop, we translate every sticky note from the map into a properly structured user story. In Agile software development, a user story is a brief description of a desired feature that is written from the perspective of an end-user, and that captures user outcomes that the feature is meant to support. A user story follows a prescribed format:

As a [user type], I want [feature] so that [benefit].

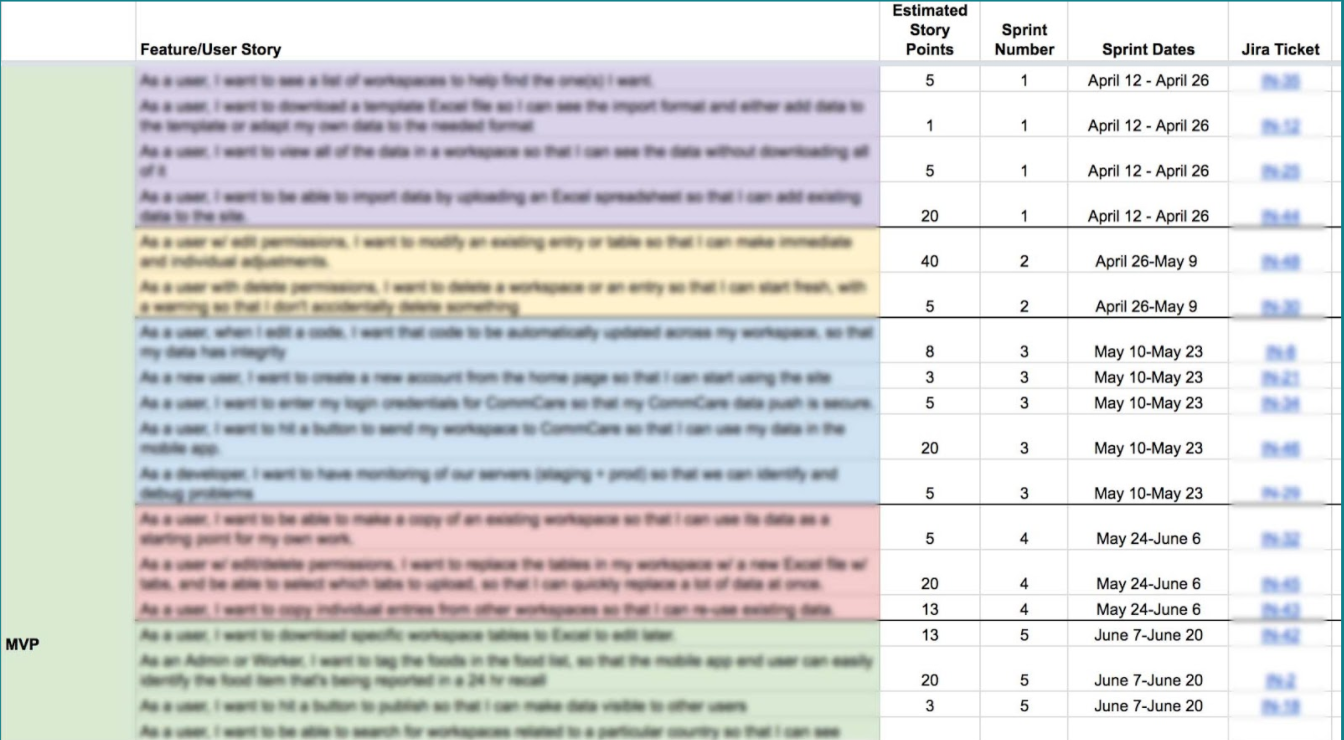

We write user stories as a team on index cards and assign acceptance criteria to each of them. (Acceptance criteria are conditions that a feature must satisfy to be accepted as done or completed.) User stories are then estimated by the development team. There are a variety of Agile estimation techniques available. We generally use Planning Poker at Caktus but at the beginning of a project, there are too many backlog items to estimate for Planning Poker to be effective. We have found that in those cases, Relative Mass Valuation works well. Using this technique, the team first arranges the user stories in order of their relative size, from small to large level of effort, and then assigns story points to each one using a modified Fibonacci sequence. The result is a fully estimated initial product backlog, which will allow the product owner to create a release plan.

Here is what a set of estimated user stories could look like:

Creating a High-Level Release Plan

The product owner ranks the estimated user stories by priority, taking into account the business value and relative effort of each one, to best take advantage of the development time available. If the team’s velocity is already known, the product owner can divide the major features into rough sprints to create an initial release plan:

The product backlog, and by extension the release plan, evolve constantly as the project progresses: priorities change, scope is added or reduced as feedback is gathered, stories are broken down into smaller ones, etc. As long as new backlog items are estimated and prioritized, the product owner can adjust the release plan to maintain a realistic release timeframe.

Conclusion

The process from user story mapping through writing and estimating the user stories gives development teams a foundation on which to base the development effort. User story mapping is a good way to determine what user tasks must be supported and how they break down into subtasks, as well as which user tasks are not essential for the application to deliver on business and user value. Writing user stories as a team is an opportunity to articulate each story in more detail and spread the knowledge among all members of the team. Finally, estimating user stories with the Relative Mass Valuation technique is an efficient way of sizing many stories in one estimation session by comparing them to each other.

We have found the process useful, but we have also learned some lessons:

- During user story mapping, the stakeholders’ understanding of the project may evolve and by the end of the activity, the user stories identified at the beginning may change accordingly. In these cases, it is important to revisit those stories at the end of the discovery workshop to confirm or adjust them in light of the newly gained understanding.

- Writing user stories with team members who have not participated in the discovery workshop can be challenging. In future, we may include a separate workshop debrief session to bring the entire team up to speed on the findings from the discovery workshop before we set out to write user stories.

- A high-level release plan can be a helpful tool offering an initial timeline for the product release. However, it can become an impediment if its transient nature is not fully understood. In Agile software development, it’s paramount that a high-level release plan such as the one shown here not be treated as a definitive schedule, but rather as an initial take on a possible order of work. As soon as the work begins, that order will change as new information about the project is revealed through the development process.

To learn more about UX techniques used at Caktus, read Product Discovery Part 1: Getting Started or Product Discovery Part 2: From User Contexts to Solutions.